Dark Patterns, Data Brokers, & De-identification

Life on the internet has become somewhat of a non-stop robbery. We all get got by data thieves on the internet every day. The Irish Counsel for Civil Liberties estimates that an average person in the United States has their data exposed up to 747 TIMES PER DAY through real time bidding on your internet browsing activity. While we do have some laws that cover data belonging to EU citizens and California residents, most of our innermost internet experiences are being bought and sold in a free for all, with some even referring to data as “The New Oil.” And what an apt description.

If our laws do not address the following loopholes that allow data to be exfiltrated and sold, this exploitable resource will be extracted at all costs… Regardless of the destruction it causes.

Dark Patterns

Dark patterns are manipulative practices built into websites. They exert control over users’ decision-making by design. These techniques push users towards taking actions against their interest, including disclosing data they would not otherwise share. Companies use dark patterns to reap short term benefits. In some cases they may trick you into clicking “Agree to all” in their privacy settings. In others, they may even reconfigure your privacy settings without your knowledge.

Use of dark patterns has become a common practice in UI design. However, it’s far from the best way to grow your business – and with increasing regulation, it’s swiftly becoming a liability. Phasing out dark patterns in favor of ethical design allows you to build trust with your user base.

As lawmakers start regulating, companies are going to have to ditch these deceptive practices to stay in compliance and in business. This article from UX Planet identifies 5 common dark patterns, along with suggestions for user-friendly alternatives.

State and federal regulators are starting to address the use of “dark patterns.” According to Reuters, “businesses will likely need to reexamine elements of their products, such as user interface and other designs, to ensure compliance.” Eliminating deceptive practices in web development is an important step forward in ensuring consumer privacy.

Data Brokers

Data brokers are companies that purchase, collect, and process consumer data to license to a third party.

We may know that a “trusted” app is collecting data from us, but the obscure 3rd, 4th and 5th, (…) party supply chain created by data brokers means that we are rarely aware of how that data is bought and sold. Three major data brokers – Cuebiq, X-mode, and Safegraph – purchased precise location data from Life360, a widely-used location tracking app for families to stay in touch. These data brokers then sold that location data, which pertained to children and adults, to US agencies including the CDC and even the Department of Defense.

Data brokers claim the data they accumulate about you is “anonymous.” As this excellent Wired article by Justin Sherman points out, the larger the data set is, the easier it is to link the data to an individual. For example, researchers at UT Austin were able to match Netflix users’ “anonymized” movie ratings to their IMDb profiles. This identified the users as well as “their apparent political preferences and other potentially sensitive information.”

Oregon’s Consumer Privacy Task Force, which I am relieved and grateful to be a member of, almost passed a bill in Oregon to regulate data brokers, but it was struck from the docket at the final stage.

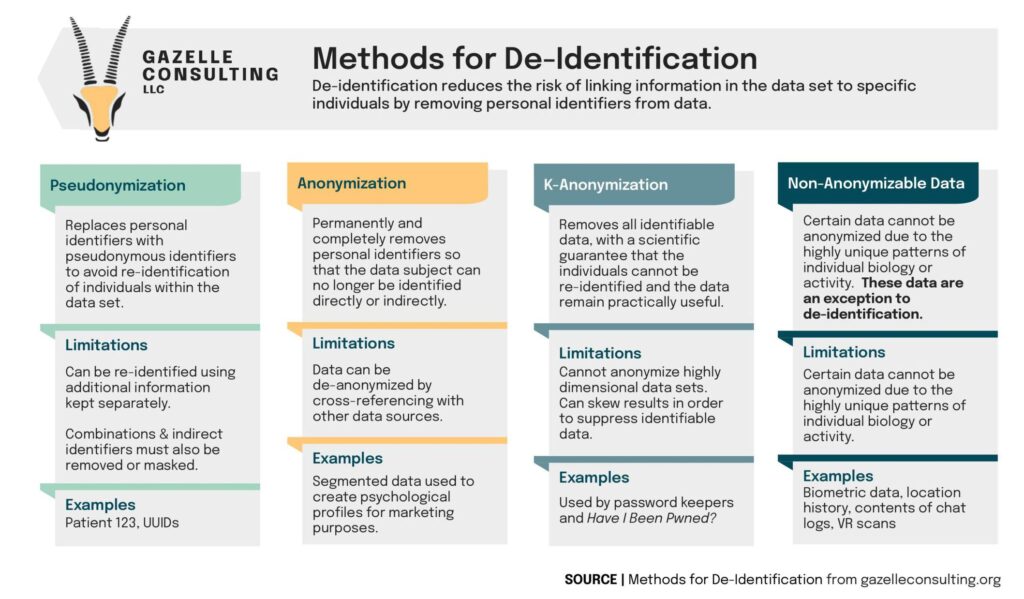

De-identification

Companies collecting and selling our data often respond to privacy concerns by de-identifying the data. But if we are talking about data sets containing hundreds of “de-identified” data points about an individual, is it even possible to truly de-identify that data?

A growing and commonly ignored category is non-anonymizable data; data that is so unique that there is no way to decouple it from the individual it belongs to. This includes biometric data, location history, and many linked data sets that describe an individual’s preferences or behaviors.

There are many ways to de-identify data, but the more meaningful data that gets removed, the less usable the data becomes. Each method has different limitations and create differing levels of re-identification risk. The image below illustrates the different methods of de-identification.

We may be approaching a reality in which de-identification is no longer an appropriate safe harbor for using data without restriction. Our concept of data that needs strict protections is expanding, along with the reach of technology into our private lives.